26 June 2016

Post-graduation limbo: those etheric spaces between completing a degree and using it. There's a wide variety of work I could do with my skill set. I like to grow plants, get creative with digital and analog media, explore ecosystems, and learn new skills. Heck, I like to learn almost everything. I like working with my hands. I hate classrooms. Most of the jobs I've applied for are consulting firms that do environmental surveys to ensure parcel sites are buildable, things like that. I applied to a few video game companies for narrative design, because making video games was my dream job when I was a kid. Well, one of them. I also wanted to be a scientist, author, visual artist, movie star, rock star. And so on. But whether it's video games or field biology, everyone is only looking for applicants with years of experience already. You can't get experience without being hired, and you can't be hired without prior work experience in the field. Can you blame them? Who wouldn't hire a proven specialist over an untested newcomer? But I've been learning ecosystems since before kindergarten. I never changed my major. I've got hands-on experience in hydrology from watching rainwater deepen the ditch for twenty years at the old Woodscreek house. My first experience in microbiology was in first grade, when I tested Pringles crumbs in solution as a substrate for fungal anaerobes. My mom never lets me forget that, because my teacher told my mom she should ask me about an experiment that might smell bad if she didn't find it in time. It was in a small, sealed jar in the garage. No harm done.

The positions for biology work proper are slim: or more accurately, only a few subdisciplines have a vigorous labor market. Biomedicine and computational biology are "in". Without an intensive molecular biology background, I am locked out of most industry jobs. On the other hand, I wouldn't want to be cooped up in a lab running samples all day so it's just as well. Jobs in the macrobiology field are few, and they tend to be in the middle of nowhere. GIS (Geographic Information Systems) is highly requested by employers. It's more commonly used in geologic studies, and the geology jobs are in greater demand than macrobiology. It's good that I took several geology classes, because that makes me a more competitive hire. Although to my young mind, both disciplines sprang from a single primordial experience: watching PBS shows about dinosaur fossils. At that point, it did not occur to me that academic communities divide the of study for the creatures separately from the study of the rock substrate. Or that paleontology is a tiny, obscure field in academic sciences and negligible in private industry. In my mind, a scientist went out into the field, took notes, and solved hows and whys of enigmatic natural phenomena. Going out and solving mysteries of the universe, both big and small.

Here is an enigma that should have been presented to the young mind: "See those humans out there in the field? As plants aggregate around water sources, so do humans gather around sources of money. From where originates the flow of income that feeds these humans?"

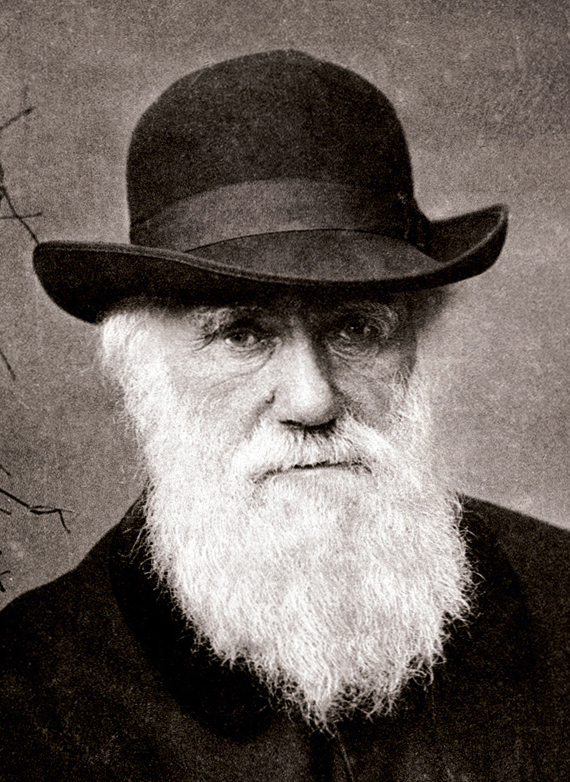

If you ask me who paid scientists, I would probably have said the government, National Geographic, and all the grateful crowds hungry for scientific discovery. Those early impressions more closely match the job description of a nineteenth-century naturalist than a 21st-century one. In the early days of science, naturalists were often British aristocrats. People like Charles Darwin and Joseph Hooker had the money to fund their travels across the globe. Others, like Arthur Wallace and Henry Bates, sold novelties from their travels to wealthy Britons to finance their expeditions. The job market for adventurers has never been large, but you can still apply to be an explorer for National Geographic.

An update on the Mojave veggies: The Siberian kale is still small, but there is one very robust turnip. And a bean plant just emerged today. I'm really fascinated to see what that one looks like in a few weeks. I've only watered the soil a little bit every five days, so the soil stays very dry. It's fun to look at. The biggest planter so far is a big Mason jar. I wanted to be able to see clearly differentiated hydration layers through the glass, but I don't know if this jar is deep enough to do that. At any rate, I initially saturated this jar when I first planted. It percolated really well with the first soak, but silt sediments rose to the top and it didn't percolate so well after that. So I'm being gentle with the watering not only to mimic parched desert conditions, but because I don't want the silt layers to choke the little seedlings. In Chattanooga, the clay would expand when it got hydrated, and that did damage the stems of many of the vegetables in their infancy. Unfortunately, I don't have pictures today because my phone charger stopped working last night.l;plop; (That was Titus walking across the keyboard. He made the word "plop"! His first word.) For all the Titus fans reading this, he didn't take the move to Colorado so well. He used to get all his energy out by bullying Ashley's two cats. Now that they're gone he just wants to cause trouble. He's grumpy more often than not and started excreting outside the litter box. I've never had such a frustrating experience with an animal. Cats belong outside, I've decided.

He can still be cute though.

Back